And Awe Came Upon Everyone

It’s happening again.

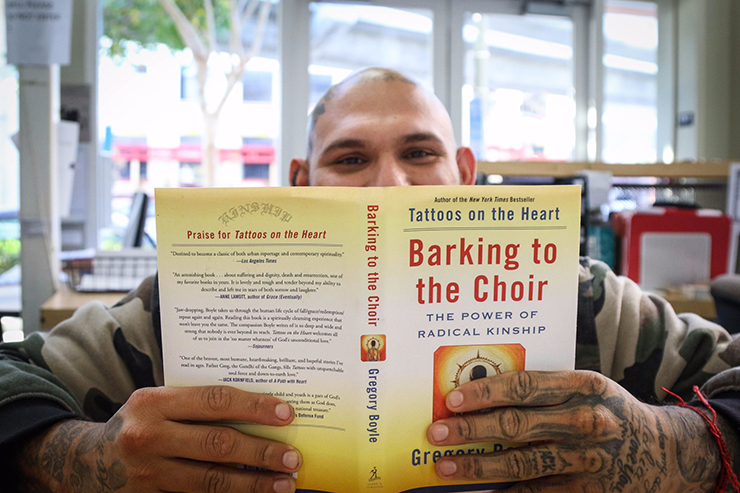

I’m finding myself underlining everything in Father G’s newest book (Barking to the Choir).

The first few pages of chapter 3, “And Awe Came Upon Everyone,” goes like this…

Lately, I’ve been taking a leisurely stroll through the Acts of the Apostles. This section of the New Testament is not only a quaint snapshot of life in the earliest Christian community but also a lesson in how to measure the health in any community at all. When you read Acts through this lens, things start leaping off the page. “See how they love one another.” Not a bad gauge of health. “There was no needy person among them.” A better metric would be hard to find.

There is one line that stopped me in my tracks: “And awe came upon everyone.”

It would seem that, quite possibly, the ultimate measure of health in any community might well reside in our ability to stand in awe at what folks have to carry rather than in judgment at how they carry it.

Homies often say, “I was raised on the streets,” but Monica truly was. Homeless, a gang member, and a survivor, her behavior at Homeboy can often be alarming. She once kicked in our glass front door. On another particularly wild rampage, she went into our kitchen and began to gulp down a purple all-purpose cleaner called Fabuloso. (“Fabulosa” later became her nickname among the homies).

Despite these outbursts, I still hope she’ll get caught up in the rapture of the Holy Trinity—Recovery, Meds, and Therapy—but you take victories where you can. I once corrected her for speaking with some harshness to one of the trainees.

“But that’s why I told her to ‘Shut up,’ she said, stone-faced, “instead of ‘Shut up, you f***ing bitch.’” Progress. Awe compels us to try and understand what language her behavior is speaking. Judgment never gets past the behavior.

After another incident, Father Mark tells her, with tenderness, “I wish I could adopt you.”

“You would not want me for a daughter,” she tearfully replies.

“Course I would,” he says. “It would never be boring.”

Mark knows he can’t carry what Monica carries. But he can carry her.

Once I was invited to speak to six hundred social workers in Richmond, Virginia. Often I’ll say yes to invitations like these without studying the details too carefully. I assumed the Richmond event was some keynote or lunchtime address, but when I later read the not-so-fine print, I realized that I had committed myself to a daylong in-service on gangs, from 9:00am to 5:00pm—and I was to be the only speaker. So I invited two trainees into my office, DeAndre and Sergio. “Look, you’re flyin’ with me to Richmond, Virginia,” I tell them. “I want you to get up and tell your stories. Take your time… cuz we got a long-ass day to fill.”

Sergio was in his mid-twenties, a tattooed gang member who had served considerable time in prison. He also had been homeless for a stretch and an active heroin addict for a longer one. I knew patches of his backstory: drinking and sniffing glue at eight, which eventually led to crack, PCP, and finally heroin. He had been first arrested at nine for assault and breaking and entering, jumped into a gang at twelve, and did two and a half years for stabbing his mom’s boyfriend, who tried to abuse him. Sergio began at Homeboy Industries in what we call “the humble place” —the janitorial crew—but in time he became a valued member of our substance abuse team, now solid in his own recovery and helping younger homies try sobriety on for size.

As he stood before the audience in Richmond, Sergio began his story in an offhand way. “I guess you could say my mom and me, well, we didn’t get along so good. I think I was six when she looked at me and said, “Why don’tcha just kill yourself? You’re such a burden to me.”

Six hundred social workers gasped in unison. Sergio fanned his hands like he was trying to put out a fire. “It sounds way worser in Spanish,” he said reassuringly. Everyone laughed. We all got whiplash moving from gasp to laugh. He’s one sentence into his story and we all need a laugh.

“I think I was, like, nine years old,” Sergio continued, “when she drove me to the deepest part of Baja California, walked me up to the door of this orphanage and said, ‘I found this kid.’” He paused, his voice beginning to quietly buckle. “I was there ninety days before my grandmother could get out of my mom where she had dumped me, and my grandmother came and rescued me.”

He searched for what to say next. “My mom beat me every single day of my elementary school years, with things you could imagine and a lotta things you couldn’t. Every day my back was bloodied and scarred. In fact, I had to wear three T-shirts to school each day. The first one cuz the blood would seep through. The second cuz you could still see it. Finally, with the third T-shirt, you couldn’t see no blood. Kids at school would make fun of me. ‘Hey, fool… It’s a hundred degrees… Why ya wearin’ three T-shirts?’”

He paused again so his emotions could catch up to him, momentarily knocking the wind out of his speech. For a time he seemed to be staring at a piece of his story that only he could see.

“I wore three T-shirts,” he finally said, swallowing back his tears, “well into my adult years, cuz I was ashamed of my wounds. I didn’t want no one to see ‘em.” Then he suddenly found a higher perch upon which to rest. “But now I welcome my wounds. I run my finger over my scars. My wounds are my friends.”

“After all,” he continued, barely getting out the words, “how can I help others to heal if I don’t welcome my own wounds?”

And awe came upon everyone.

The fourteenth-century mystic Julian of Norwich thought that the truest and most authentic spiritual life was one that produced awe, humility, and love. But awe gets lost in that triad. We are at our healthiest when we are most situated in awe, and at our least healthy when we engage in judgment.

Judgment creates the distance that moves us away from each other.

Judgment keeps us in the competitive game and is always self-aggrandizing. Standing at the margins with the broken reminds us not of our own superiority but of our own brokenness. Awe is the great leveler. The embrace of our own suffering helps us to land on a spiritual intimacy with ourselves and others. For if we don’t welcome our own wounds, we will be tempted to despise the wounded.

Wow. I need this book.

At 6 my mom said, “Why don’t ya kill yourself. You’re such a burden to me.”

With a 6yr old of my own, this messed me up reading it.

Too many of us are blind to the reality of what some people’s stories are and why they do what they do. Why they are who they are. BUT…they’re not defective and/or anymore broken than I am…maybe I just hide it better.

We all need each other…to realize that we really aren’t that different. These stories are a reminder that A LOT is going on behind the masks we all wear and my first response should be compassion not judgement. What we all need is another chance at redemption.

“another chance at redemption.” I like that Kyle.

Absolutely, yes, Kyle! Thank you.

“Oh God! May my heart feel like yours in the moments of my days.” I don’t know if there’s a more important prayer for me to pray. Thanks for sharing.